Том Хиддлстон. Глава третья / Tom Hiddleston. Chapter III

Сообщений 61 страница 90 из 240

Поделиться622012-12-25 20:46:36

HaliGaliKrishna написал(а):

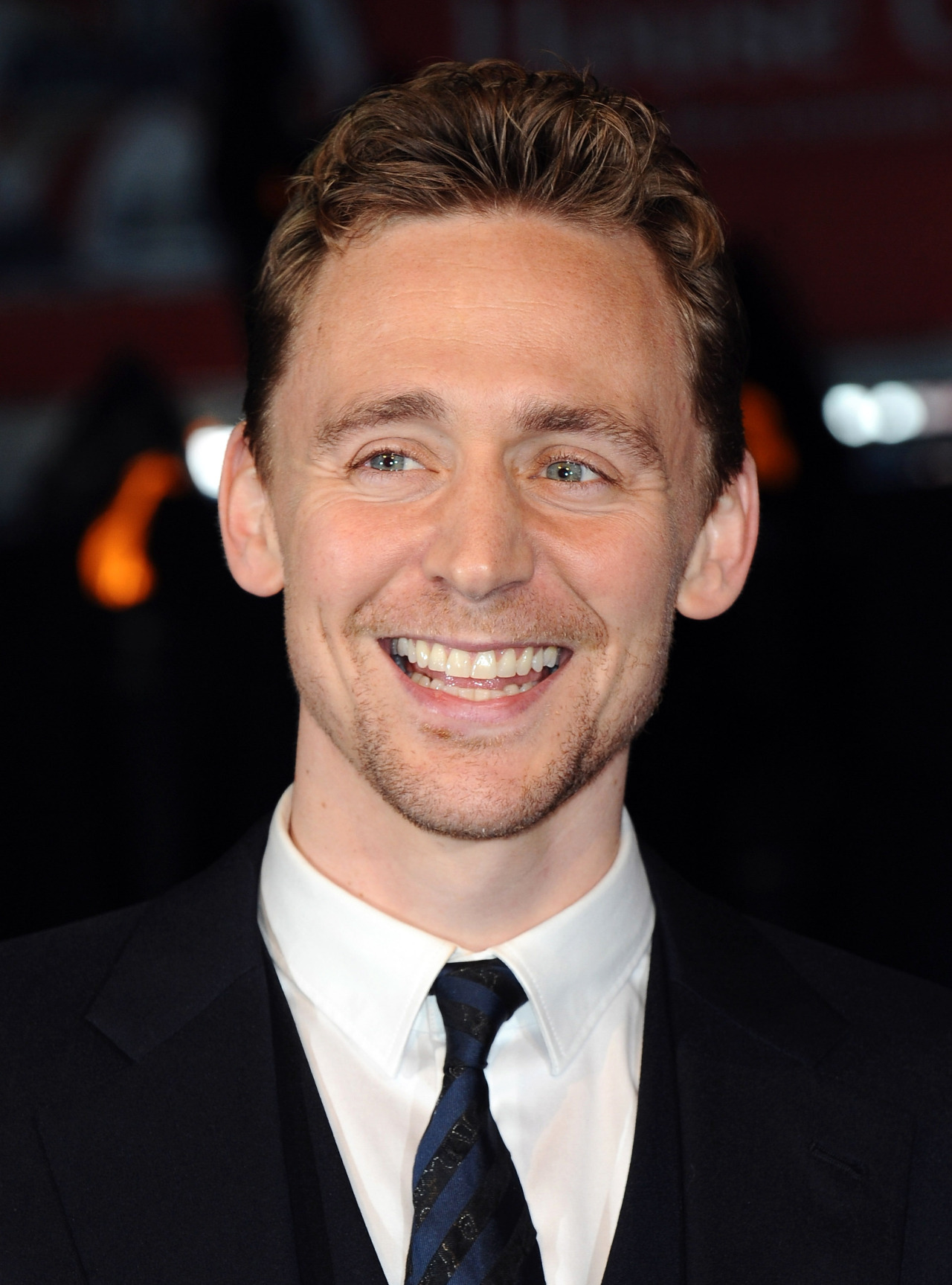

В этот раз галстук у Тома какой-то странный. Так и хочется потрогать материал из которого он сделан

ага, ага, ну конечно. потрогать. галстук. ну-ну

а вообще, надо сказать, костюмчик-троечка сидит отлично

А что, я б тоже потрогала гастук. И без всяких там задних мыслей. Ибо меня гаслстучек, точнее, материал, из которого он изготовлен, очень заинтриговал.

А вообще, на Томе все костюмы отменно сидят.

ну, как я поняла из этой заметки, он не то что бы уже пошел вставать по другую сторону камеры, он это брякнул, оказавшись в жюри конкурса короткометражек, что, мол, тоже бы вот хотел снимать свое кино, но времени у него на этой ужас как нет, и всё такое))) в общем, из вежливости и поддержать основное направление беседы, хых))

я так думаю, в ближайшем будущем этого самого времени на режиссуру у него и не появится, сниматься надо ))

Ну, может, так сказать такой план на будущее. Пройдут годы, Том постареет, быть может, ему надоест сниматься, и заделается режиссером. А может быть, и будет снимать фильмы, да сам в них играть, аки Клинт Иствуд

Том принял участие в озвучке мультсериала "Робоцып". Его голос можно услышать в истории с Лораксом, которая начинается с 7:48. Том читает закадровый текст.

Ну не знаю, вот как-то не воспринимаю я особо этого робоцыпа. Одно время начинала смотреть, но не зацепило. После просмотра данного эпизода (естественно ради голоса Тома), я своего мнения не изменила...

А что за девушка с декольте?Кто она? Вроде ничего такая, симпатичная)))

Поделиться632012-12-25 23:09:00

А что за девушка с декольте?Кто она?

Имя забыла, но девушка актриса и с Томом обучалась актерскому мастерству)))

В интервью журналу Empire Том Хиддлстон рассказал, что Кевин Файги рассматривал его режиссера)))).

"Да, такое было. Помню я шутливо спросил у Кевина могу ли я стать режиссером и он ответил мне "У тебя есть примерный материал?", я сказал что нет, а он мне говорит "Если ты покажешь свой отснятый материал, я подумаю." Хорошо, что я не стал режиссером. Эта работа требует большой ответственности, хотя возможно она могла мне понравится."

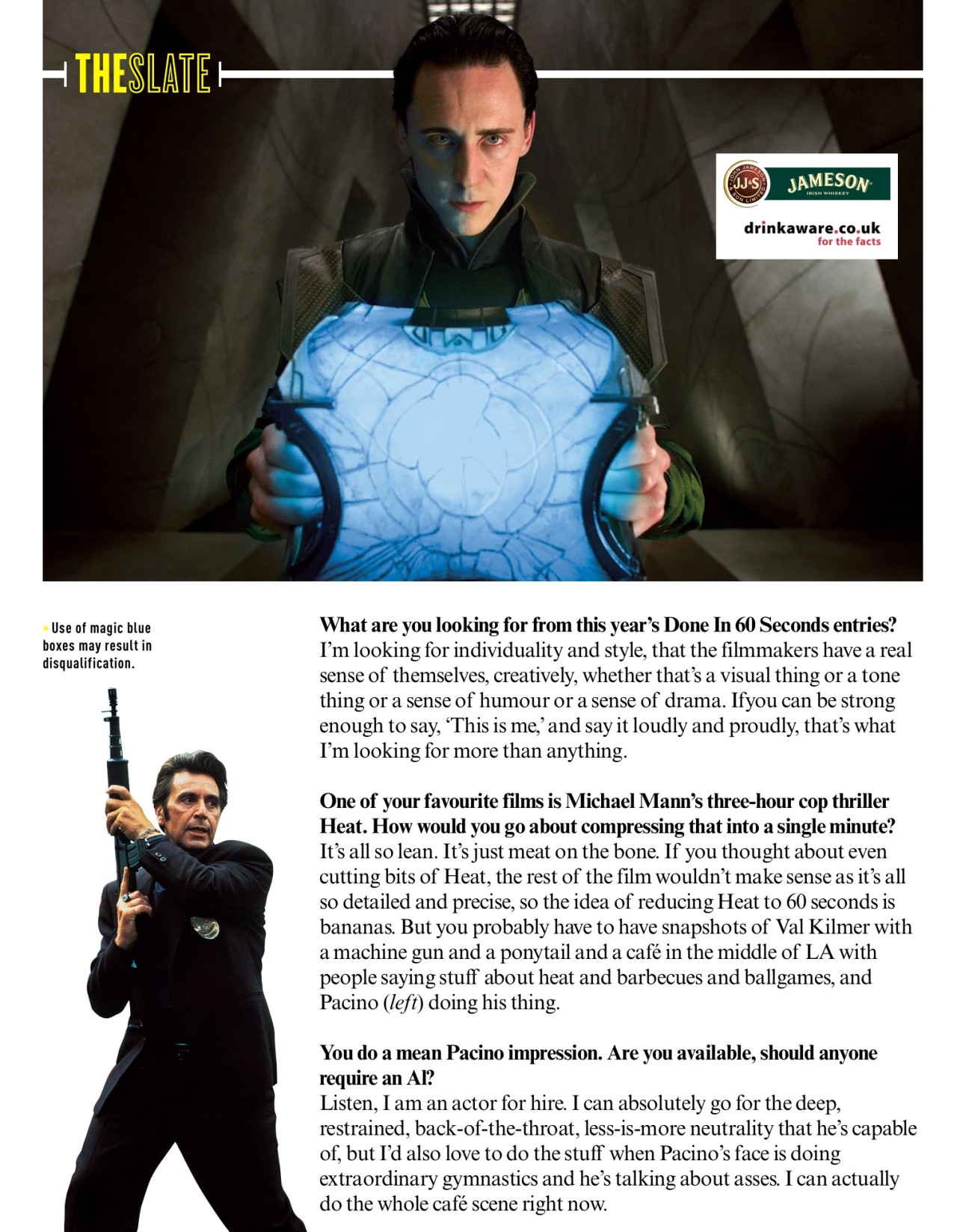

Статейка))

‘After Hours’ Celebrates Kristen Stewart, Tom Hiddleston And Tequila In 2012

Best Improvisation (With an Inanimate Object) - Tom Hiddleston Perhaps the most fun I had on a shoot all year (it certainly was the longest) was with the mad genius that is Tom Hiddleston. We scripted “Loki’D” to be a fun riff on Tom’s “Avengers” persona, of course, but what we never expected was that Tom would be so game, so open and so consistently hysterical. The coup de grace was a small improvisation in which he called his fake mustache Wendy, which proceeded to help spur on an astounding Internet meme. Go on, google “project Wendy” for fun and marvel at the creativity out there.

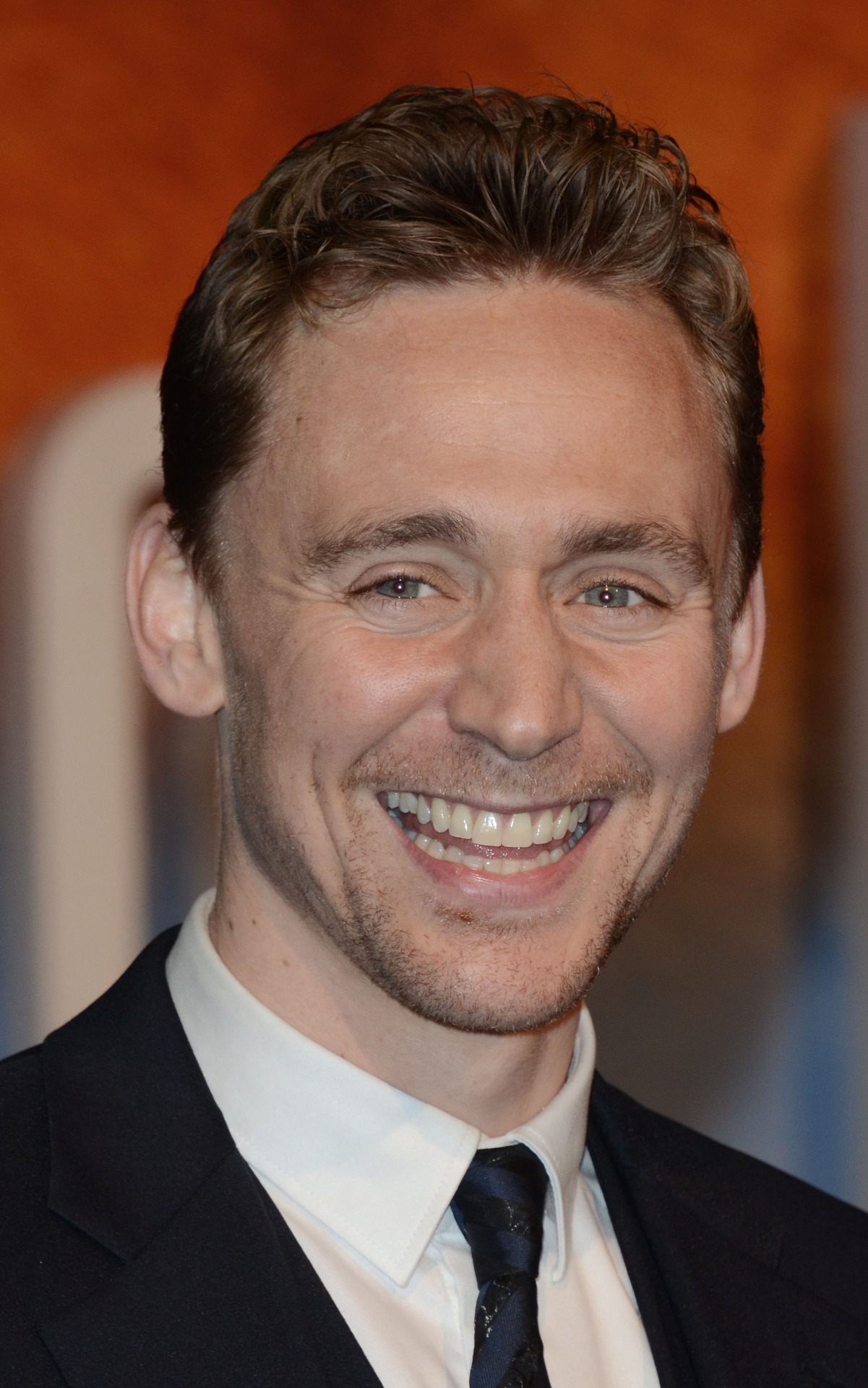

Еще одно брутальное фото))

Поделиться642012-12-27 15:45:31

а так хорошо всё начиналось...

Поделиться652012-12-27 22:54:57

а так хорошо всё начиналось...

Loki'd продолжает выносить мне мозг!  Хотя это видео имеет ряд преимуществ))) Во-первых, очень радует настоящий смех Тома после этого Loki'd смеха. А во-вторых, на Тома запрыгивающего на стол я могу смотреть вечно!

Хотя это видео имеет ряд преимуществ))) Во-первых, очень радует настоящий смех Тома после этого Loki'd смеха. А во-вторых, на Тома запрыгивающего на стол я могу смотреть вечно!

Ох уж эти брови!

В топ-5 суперзлодеев 2012 года том занял первое место! Я даже не сомневалась)))

1. Loki

It wasn’t even close. The Asgardian God of Mischief blew every single competitor out of the water with 83.8% of the vote, besting Bane by thousands. Credit where it’s due: Joss Whedon wrote one hell of an adversary for Earth’s mightiest heroes, and Tom Hiddleston played him to perfection, evolving his tragic character from the days of “Thor” to the mighty heights of “Avengers.” Combine that with the feverish fan following that is Loki’s Army, it’s no wonder that he stands strong as your villain of the year.

Сам себе бабочку поправляет

Отредактировано HaliGaliKrishna (2012-12-27 23:01:37)

Поделиться662012-12-29 16:58:31

Хотя это видео имеет ряд преимуществ

ох, не знаааааю, не знааааааю....... )))))

В топ-5 суперзлодеев 2012 года том занял первое место! Я даже не сомневалась)

а кто еще был?

что-то мне с разбегу злодеи этого года не вспоминаются никак

ну блин.... о! Ящер в Челопуке, которого я до сих пор не посмотрела, и Кобальт в Миссии невыполнимой! всё, больше ниче не помню

а зато тумблер медленно, но верно избавляет меня от необходимости рисовать всем шапки

поэтому просто несу. с Наступающим!

Поделиться682013-01-03 21:01:55

Язычок!

Несколько новых фотографий со старых мероприятий)))

Том умеет правильно влезть в кадр)))

Не знаю уж, старые это интервью или старые-новые, но раз появляются в последнее время на тумблере, то пусть будут))) Лишний раз на Тома полюбуемся)))

Поделиться692013-01-15 11:37:32

прелестные аватарки!  спасибо автору!

спасибо автору!

Поделиться712013-01-16 09:20:52

Вот эта фотография меня как-то пугает!

ооооо, отличная, нет, просто потрясающая работа, очень нравится!

вот еще ролей бы таких теперь

ну, а если кто все же испугался, то вот у нас есть немного повеселиться

Фригг: Мальчики, давайте, Мойдодыр: "Одеяло..."

Локи: Убежало....

Тор: Ха-ха-ха! Трусливая тряпка! Беги-беги быстрее, пока я тебя не догнал!

Фригг: Наша Таня громко плачет. Уронила в речку....

Тор: МОЛОТ.

Фригг: Неправильно. Уронила в речку...

Тор: МОЛОТ.

Фригг: Да нет же. Уронила в речку....

Тор: МОЛОТ.

Фригг: Уронила....

Тор: МОЛОТ.

Локи: .....

Фригг: Не молот, дорогой. Но тоже на "м".

Тор: Меч?

Фригг: Крошка-сын к отцу пришел и сказала кроха....*выразительно глядя на Тора*

Тор:*запинаясь* Что такое.... хорошо.... что такое...

Локи: Перекрестность пространственного континуума между мирами?

Фригг: ....

Локи: Прости, мама.

Фригг: Муха-муха-цокотуха - позолоченное брюхо. Пошла муха на базар и купила...

Тор: Доброго коня.

Локи: Справочник по древним рунам.

Фригг: Самовар.

Тор: Нуу, так неинтересно...

Фригг: Ладно, хорошо. Однажды в студеную зимнюю пору я из лесу вышел....

Тор: Громить Ётунхейм!

Локи: Был сильный мороз!

Фригг: Молодец, Локи. Гляжу, поднимается медленно в гору....

Тор: Мой враг - царь Лофей, а с ним все его войско! Но я их ррраз! Рррраз! И головы посшибал, руки поотрывал, и ноги на палку понакручивал и всех положил!

Локи: Лучше было подготовить ловушку, и чтобы они сами туда попадали.

Тор: Так только трусы поступают! Надо было победить их в честном бою!

Локи: Нет, устроить ловушку.

Тор: В бою!

Локи: Ловушку!

Тор: В бою!

Локи: Ловушку!

Фригг: В лесу раздавался топор дровосека...

Тор: АГААА! Я же говорю! Топор! Я выиграл!

Фригг - Одину: Мне кажется, на утреннике у нас могут возникнуть определенные проблемы.

нашла тут

Поделиться722013-01-18 21:28:24

А кто тут у нас самый сексуальный мужчина?)))

Tom Hiddleston on being voted Total Film’s Sexiest Actor Right Now: interview

“It’s insane…”

You voted, and the results of Total Film’s Sexiest Stars In Movies Right Now poll have been revealed.

You can see thelist of your favourites laid out in full in issue 203 of Total Film magazine, which is available now on newsstands, iPads and Android devices.

Tom Hiddleston topped the men’s category, pipping the likes of Robert Pattinson and Ryan Gosling to the title.

Winning the vote by a sizeable margin, Hiddleston has amassed an army of fans since his meteoric breakout playing the deliciously despicable Loki in Thor and The Avengers. That he’s backed up those blockbuster turns with considered roles for some of today’s most respected directors (Midnight In Paris, The Deep Blue Sea, War Horse, Only Lovers Left Alive) hasn’t harmed his credentials one bit.

We spoke to Hiddleston to find out what he made of being voted your Sexiest Actor Right Now…

What’s it like to beat the likes of Robert Pattinson, Brad Pitt and George Clooney to the title of Total Film’s Sexiest Actor?

“It’s insane. It basically doesn’t make any sense. When I was a teenager, my sister had a poster of Brad Pitt from Legends Of The Fall on her bedroom wall. I also thought it was generally accepted that George Clooney was some kind of gold standard? And doesn’t Robert Pattinson inspire mayhem and delirium wherever he goes?

“I suppose my question is: Are you sure? If you are sure, then I am very flattered. VERY. Thank you, ladies. You are women of impeccable taste and style. My god, you know how to make a man feel good.”

Could you have ever dreamt of inspiring so many hearts to flutter when you were growing up?

“Absolutely not. My sister used to say I had hair like a broom. She meant it in a nice way. In the nice way that sisters do. She was probably right. But sincerely, no.

“One of the great flaws that we all share is that we think everyone else is cooler, everyone else is sexier; everyone else has all the answers. That was me too.”

A dangerous edge is often equated with being sexy… which surely makes Loki super-hot! Do you think of him as devilishly attractive when you play him?

“No! I defer credit entirely to the hair and make-up department. I just play the character: his intellect; his lone wolf independence; his mischief. Mischief is danger, I suppose; mischief is edge.

“The strangely admirable thing about Loki is that he doesn’t give a damn what anyone else thinks. I’ve always found that quality really sexy in women. Self-possession. Quiet confidence. An acceptance of difference. A certain… mischief. A sense that things could be a little “exciting”. I think I should stop there!”

Ссылка

Поделиться732013-01-18 21:32:52

Дела благотворительные...

Tom Hiddleston teams with UNICEF in a fan-interactive charity mission

Next week, our issue 5 cover star, blockbuster lothario Tom Hiddleston, will be trading cameras for camping equipment. In partnership with non-profit organisation UNICEF, he’ll be trekking and doing charity work across remote, exotic terrain as one of their high profile supporters.

This means that all the while he’ll be documenting his exploits and ordeals in the form of video blogging, diary writing, and direct interaction with his Twitter followers, for the entirety of the trip in real time. The location will remain undisclosed until he gets there, but we’re hoping it’s somewhere hot and tropical. He’d really suit the bandana and machete look.

The hashtag for all trip messages will be: #Tom_UnicefUK

Twitter accounts to follow are @twhiddleston & @unicef_uk

Новое фото самого сексуального мужчины из Total Film))) Большоооооое!)))

Ну и фото из фотошута того же Total Film в хорошем разрешении))

Поделиться742013-01-20 00:21:44

Новое фото с твиттера с такой надписью: Just had my briefing from @UNICEF_uk: suncream & mosquito net required! Any more guesses where I’m going?

И свежие фотографии от 18 января)))

Поделиться752013-01-21 09:43:09

А кто тут у нас самый сексуальный мужчина?))

да ну нафиг

Tom Hiddleston teams with UNICEF in a fan-interactive charity mission

молодец. вот видео по поводу. как ныне сбирается....

Поделиться762013-01-22 21:18:48

вот видео по поводу. как ныне сбирается....

Классно собирается, спасибо!)))

А вот проводы))

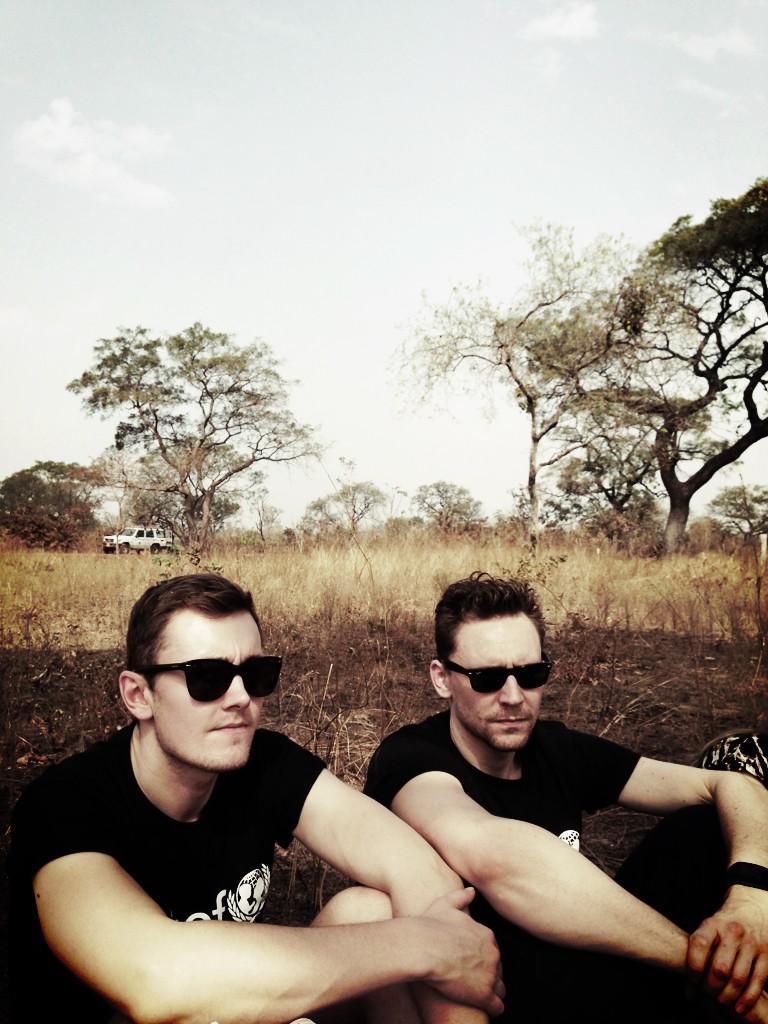

А вот и первый день Тома в Западной Африке))) Все с твиттера Тома.

А вот еще Том выложил всякие пейзажные картинки)))

Фанаты среагировали на поездку Тома вот таким вот творчеством)))

Отредактировано HaliGaliKrishna (2013-01-22 21:20:42)

Поделиться772013-01-24 03:49:23

Фанаты среагировали на поездку Тома

ага, про адвэнче тоже встречалось мне  на рисунке очень похож, очень!

на рисунке очень похож, очень!

автор офигенно точно уловил внутреннюю суть

и вот сидит наш путешественник, практически как Ленин, в москитной сетке, и пишет дайри

а вот и сам дневник

Tom Hiddleston’s Guinea field diary: Day 1

Tom Hiddleston, 01-23-2013 2:29 PM (x)

This week, actor Tom Hiddleston set off on his first journey with UNICEF UK to Guinea in West Africa. Tom will be meeting with Guinean children, families and communities. He’ll also be visiting several UNICEF projects, and finding out about our work in child protection, education, and water and sanitation.

It hits you like a wave. It envelopes you like a rolling fog. It washes over you like the tide. Heat. West African heat. Guinea. It’s hot.

I’ve come from snow. From a world of airport closures and flight cancellations, from slippery pavements, woolly hats and collars raised against the chill.

But when I landed only hours ago in Conakry, Guinea, after clearing customs I stepped outside into the evening air. The heat. The unmistakable scent of sub-Saharan Africa. Noise. Smells. Traffic. Not western metropolitan traffic, organised into lanes of air-conditioned portals of music and luxury, but the tangible, palpable energy of traffic in the developing world: human, animal, mechanical – all surging forward in a rushing tide, in an order invisible to the western eye, simply because it looks initially like chaos.

I didn’t sleep. I couldn’t. I was too excited. I stayed up the night before clearing my inbox and cleaning the house. 4:30am. A car arrived to take me to Heathrow. I met up with the team: Louise O’Shea and Pauline Llorca from UNICEF UK, Harry Borden our photographer, and my friend Luke Windsor, who introduced me to Pauline a year ago. The first leg was quick: London to Paris, where we met Julien Harneis, the UNICEF representative in Guinea for the last three years. From Paris Charles de Gaulle our Air France jet took off for Conakry.

Then I slept. When I woke up we as we were descending into Nouakchott, Mauretania, where we were due to drop a few passengers. Outside my cabin window: desert. Miles and miles of it. Massive and ancient.

By the time we had arrived in Conakry the sun had set and it was dark. We jumped into 4x4s but we’d only been in the car for half a minute before Julien asked the driver to stop. Across the road from the arrivals terminal was a car park littered with children. Islands of them. Not playing together. They were sitting on the ground: solitary and still. They were reading. Because, as Julien explained, that is one of the only safe places for them to learn. Here, there is electric streetlight for them to read by, and at night they don’t have do chores or to work. Some children walk for an hour just to sit on the ground in a car park to read.

A country like this immediately collapses the walls of your imagination and pushes them back by immeasurable distances in opposing directions. It’s mind-expanding. I have felt like this on previous occasions after landing in India. Life teems from every corner and quarter. I feel as though the cardboard box of my own reality has been flattened and blown open. Now I can see the edge of the world.

We have dinner with Julien and two more team members, Felix and Pierre. We are accompanied by wild cats and bats. Over couscous and quiche, Julien gives me a potted history of the country. What I find immediately baffling is that in West Africa, here in Guinea and in Sierra Leone, nobody teaches pre-colonial history. Here, “history” begins with the arrival of French colonialism in the late nineteenth century. This means that in the collective consciousness there is no historical knowledge or narrative detail that pre-dates the arrival and structural integration of French colonial custom. Guinea declared independence from France in October 1958. Of all their neighbouring states, Guinea was the loudest voice of dissent. They didn’t want the French way of life; they didn’t want French infrastructure, French socio-political order; or French culture. They knew what they didn’t want, but they did not know – they did not have a vision for – the country they wanted to build in its place.

Not knowing what you want is a problem of the state, but it is also a problem at a developmental level. UNICEF are here to support the vision of the country in their vision, but if they lack a vision in terms of health or education, if they lack a vision of the society they want to create, it’s very difficult to help, or to know how to help.

At dinner, Julien tells me something thought-provoking. In Western Europe, reality is relatively fixed. In Guinea, reality is open to interpretation. In the west, we process and organise information so quickly and with such immediate (possibly imprecise) rigour that we respond to events, as individuals and collectively as a society, with speed and decisiveness. The BBC, the Guardian or CNN consolidate or frame our interaction with an event: be it a declaration of war, the passing of a new law, a royal wedding or an Olympic gold medal.

In Guinea, there is no news; there is only rumour. There was a noise in the village. Some say it’s a bomb, others say it was a gun-shot, others say it was a building collapsing, other still that it’s war. Perhaps this area is too big, its disparate elements too fragmented, its narrative continuity too fluid, to be understood as a whole. Guinea has been blessed with more peace than its neighbours in recent times, and seems to have avoided being drawn into military conflict. But the same principle applies: a poor nation, with a muddled sense of itself, cannot hope to build a structure that nourishes society without literally feeding its inhabitants.

It’s become immediately clear that the problems in a developing country such as Guinea are enormous, but they can be simply defined as water, nutrition, sanitation, vaccination and education.

Above all else, the children, who will inherit the future, and shape the future of this country – need clean water, iron, minerals, vitamins, inoculation against disease, and education.

You can follow Tom on his first UNICEF trip at #tom_UNICEFUK, or send questions to his official Twitter account, @twhiddleston.

нашла тут

оригинальная ссылка: https://twitter.com/search?q=#Tom_UnicefUK&src=hash

ну, и наконец Том призывает всех присоединиться к доброму делу:

"What #IF today was the beginning of the end of hunger for millions of people?" Ссылка

Поделиться782013-01-25 10:10:48

Tom Hiddleston’s Guinea field diary: Day 2

Tom Hiddleston, Thu, Jan 24 2013 2:32 PM

It’s day two for actor Tom Hiddleston on his first trip with UNICEF UK, visiting Guinea in West Africa. Tom will be meeting with Guinean children, families and communities. He’ll also be seeing several UNICEF projects, and finding out about our work in child protection, education, and water and sanitation. Read his first post here.

I must be as honest as I can. As I sit down to write tonight, I make that commitment. Over the last two days, I have experienced joy and sadness in equal measure. I have been delighted, enlightened and confused. The UNICEF team here in Guinea have given me such a comprehensive introduction to their programs for children, and their implementation of those programs, that a picture of life in Guinea is beginning to emerge. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle: one where the pieces keep moving or changing shape, which in turn alters the picture. You might be looking at it from a different angle, or at a different time of day. It depends where you got the information, and who gave it to you. You might be filling in the blanks, taking wild stabs in the dark. It’s all open to interpretation.

Nevertheless: I must be as honest as I can.

My second day in Guinea began with a visit to the National Institute of Child Health and Nutrition (INSE) in the Donka Hospital in Conakry. Immediately I was introduced to Guinea’s most experienced doctors and child-care specialists, in whose charge are some of the country’s most severely malnourished children.

Any surges of adventurous adrenalin that I had previously felt about travelling in West Africa were tempered immediately by the sight of these children. The doctors and nurses were helpful and informative about the specific details of each of the children’s individual problems, but I was simply overwhelmed by the sight of so many small infants in such great need. One small ward – about the size of a single room in a two-star or three-star hotel in the UK – housed at least twenty children, some of whom I was told had slim chances of survival. Their arms and legs were indescribably thin, their cheeks tear-stained, their skin a harrowing, slate-grey. Most shocking to me was the speed and urgency of their breathing, asleep or awake, but it was uniformly unsettled and uneven. When you see a child struggling so hard simply to breathe, it makes your heart hurt. Many of these children had lung infections, and most if not all had been admitted because of malnutrition, or an inheritance of a condition due to the malnutrition of their mothers.

The doctors here are doing everything they can, with deep reservoirs of expertise, experience, calmness and compassion, but they need more and better equipment, as well as greater capacity. In the ward of twenty children, there was one life-support machine supplying oxygen. Just one. In a room full of twenty.

One child, awake, lying still, painfully gaunt, watched me carefully as the doctors took me around the room. “Elle a la maladie,” said an advisor, “mais elle est tres attentif.” She was so attentive, so aware, her mind locked inside her body. She, like her neighbouring children, was helpless.

I am shown into a room where I find two of the smallest children I have ever seen. One was born with a terrible skin condition, due a lack of essential vitamin A, the other was born three months premature. The sight of these two children left me speechless. The skin of the first child was as dry as tracing paper.

Many of these children are admitted with chronic malnutrition. Malnutrition is a difficult idea to grasp fully until you have seen children like these. Immediately questions arise. Why? What are the causes? The UNICEF team are quick with answers: Firstly, many children are not breast-fed from birth. They are only breast-fed for a short time, and thereafter with water, which is often unclean and rife with disease. The mothers themselves are malnourished and the disease is passed on hereditarily to the child, and often, at birth there was no provision for vaccination for the child. I’ll return to these subjects again and again. These are the corner-pieces to the jigsaw puzzle, never mind the fragmentation of the bigger picture: breast-feeding, water, sanitation, maternal care & education, vaccination.

It wasn’t all bad news at Donka. I met a newborn boy, whose mother had been previously diagnosed with HIV, but the disease had not been passed on to him. He woke up as I was passing by and was full of smiles and curiosity. UNICEF supplied the treatment that protected him from being infected.

It’s also important to say that at Donka they have a cure rate of 65%. The Institute is staffed by highly skilled professionals, who work tirelessly to save lives, but there is a lack of essential medicines, and a poor supply of equipment. As Julien Harneis pointed out to me later, I am witnessing child care at a National level, in the concentrated urbanised area of Conakry. In more remote parts of the country, however, there are different solutions within the culture and practice of local communities. It’s not necessarily the children who need the attention, it’s their mothers. Help the mothers – help the children.

Before we set off on the road to visit these rural communities, we stop off to visit Project Tinafan. We drive past football pitches, past a blurred quilt of football club colours from all around the world, but we drive pastthe football. We are here to watch the circus. Tinafan is a project designed to develop the capacities and social/economic inclusion of children who may have dropped out of school, and depend on their livelihood on meagre income from unskilled labour. Tinafan uses training in the circus arts to strengthen their confidence, bolster their interpersonal skills, and help them trust each other. All of this sounds a little dry. As far as I can see, as soon as I open the car door, these children aredancing. I hear pounding drums. I see running, jumping, smiling, free-wheeling, cart-wheeling energy rushing towards me. I see fit, strong, smiling, athletes, fit to burst. The thoughtfulness brought on by what I had seen at Donka was instantly dispelled by the sheer, thrilling, joy radiating from these children. We were invited inside the gym where they train to watch a show. A band was already whipping the crowd into a frenzy, while activity billowed behind a curtain. The band consisted of at least five drummers and two xylophones and little else. Their rhythm was propulsive and electric. I’m not sure what my expectations were, but they were entirely blown out of the water. I must be as honest as I can: these children are world-class performers of astonishing athleticism and grace. The best among them, I later learned, have toured the world with circus troupes. Their performance was explosive and dizzying – acrobatics, human pyramids, trampolining, contortionists – a display of strength, flexibility and precision on a par with, if not beyond, the very best physical performances I have seen in ballet, contemporary dance, or Cirque du Soleil. They performed with raw joy. Their trainer “Prince” also teaches them how to paint, emphasising to me that how important it is for his students to understand the power of passion and positivity in creativity after the human body passes its peak.

In one morning: a picture of sickness and disease juxtaposed immediately with a picture of health and well-being. Both true. Both in need of clear-sighted, practical attention and continued support. Two different pieces of the puzzle.

We hit the road. A bumpy road of pot holes, red dust and mango trees. The red dust is bauxite, Guinea’s primary export. It’s a beautiful country. It’s hot and humid. Smoke settles in the valley like an ethereal mist, just below the tree line. It’s from the blackening of the crops, or from cooking fires from local dwellings.

There is only one main road through Guinea, and we were on it, headed east into the rural part of the country. Along the way there are various checkpoints manned by groups armed military stopping the local vehicles ahead of us, but our 4x4 vehicles are waved straight through. Nobody stops a UNICEF transport – a blindingly clear example of the kind of respect accorded to the organisation, its representatives and workers, in the entire country at every level. In other villages, women and children sitting on the side of the street applaud as we drive by. Everybody knows UNICEF’s influence and reach is important and indispensible.

After a six-hour drive, which for me passed quickly thanks to Julien’s eloquence on the problems afflicting the country, we arrived around night-fall at the town of Saramoussayah. It’s dark. Very dark. We are here to stay the night: to meet the local elders, the mayor, the doctors and teachers, and to chair a focus group with women on key family practices for child protection against disease. We are given a warm welcome. At the presentation our group to the elders of the community I’m struck by the seriousness, strength and wisdom etched on the faces of these men and women. Their sense of collective responsibility is deeply inspiring, and humbling. They are all almost exclusively teachers, doctors, nurses, or involved in the centre de santé, the health centre. After our delegation is presented, we are invited to eat. Julien sets a careful example, and asks to wash his hands before we eat. One of the most important messages UNICEF can help to communicate is this kind of habitual hygiene. Mothers should wash their hands before and after preparing food, they should wash their hands after cleaning and washing their babies and children, they should teach their children to wash their hands.

After a supper of rice, sauce, and banana, I am invited to join a Focus Group for women, chaired by the DPS, the Directrice Prefectorale de Santé, Dr Mariam Kankanlabe Diallo. I find her incredibly impressive. She seems wise and experienced, with deeply kind eyes. She commands respect in the local community because of her education. And she, like all women in the Mamou region, dresses in clothes and a headdress of brilliant colour. We are escorted away from the centre of the village, seated in a circle of benches behind some out-houses, sharing the darkness with the cows, the crickets, and the stars. We agree to touch on three subjects: washing, breast-feeding, and vaccinations. It takes a while for the women to trust us; it takes a while for them to want to talk. We have to make them feel they are in a sufficiently safe environment to air their concerns. The near pitch-black darkness adds to the anonymity.

Two things emerge that I find most surprising. The first is about breast-feeding. Some of the women confess to not knowing that it was recommended to exclusively breast-feed for as long as possible, at least up to six months. Some confess to giving their infants water after a month or two, simply on the assumption that water cannot be bad for a child, but it can especially bad when there are also local problems with sanitation and the cleanliness of water. Others confess to trying to give their child food days and weeks after birth. Some confess they didn’t breast-feed at all. What surprises me is the general lack of education about maternal care. It is not at all the fault of these mothers, many of whom are young girls. It’s simply that they didn’t know what was best. Maternal care was open to interpretation.

The second surprise is a positive one. I ask about vaccination. I’m greeted by a unanimous hum of approval when the word is mentioned – so loud and affirmative that it makes me smile. Vaccinations were unilaterally made available to everyone. Every woman confessed that the health centre stocked all the necessary and appropriate vaccines, and nobody registered a single complaint. Their children were inoculated: BCG, Polio etc. all the bases were covered. While they were still talking amongst themselves Pauline reminded me that all the vaccinations in this region of the country are provided by UNICEF. Every single one. They are not provided by the state.

This begins to illustrate the sensitive position of an organisation like UNICEF must occupy in a country like Guinea. On a developmental level, in the long term, it’s counter productive for an organisation to come in and simply fix a problem, at a macro or micro level, because as soon as they leave the inhabitants of the country are left high and dry. UNICEF has to work, crucially, alongside the authorities, (governmental and local) so that these communities can self-educate and self-sustain. UNICEF workers are trusted, and they inspire trust and confidence. And yet the humanitarian imperative is to save lives and allow people to live with dignity. If UNICEF did not make provision for vaccination, if they did not work with local communicators, if they did not fund and support health centres like the one at Saramoussaya, there would be many more children like those I saw at Donka.

Julien closes the meeting carefully. He thanks all the women for their honesty. “We can’t make any promises,” he says, “but we will endeavour to work with the authorities to help.”

In one day, I’ve seen so many different children, so many different mothers, in different communities, from so many different perspectives and angles. But I can see where UNICEF is helping. In some cases it’s with policy and programming and financial support, in other cases with direct medical help, in other cases: just being there. Turning up to help. And coming back next time. To help again. A reassuring presence: constant, listening and loyal.

And so to bed. I put on my headtorch, spray myself from head to toe with Jungle Formula insect repellant, brush my teeth, say hello to the five huge spiders sharing a room with myself and Luke, slip into my mosquito net and close my eyes. There is a lot of loud activity from a cow and her friends outside the window. I like to think they are saying hello.

You can follow Tom on his first UNICEF trip at #tom_UNICEFUK, or send questions to his official Twitter account, @twhiddleston.

Поделиться792013-01-27 08:39:17

путешествие Тома продолжается

взяла тут

Поделиться802013-01-29 06:59:22

новая порция записок путешественника

Tom Hiddleston’s Guinea field diary: Day 3

Tom Hiddleston, Sun, Jan 27 2013 10:46 AM

It’s day three for actor Tom Hiddleston on his first trip with UNICEF UK, visiting Guinea in West Africa. Tom will be meeting with Guinean children, families and communities. He’ll also be seeing several UNICEF projects, and finding out about our work in child protection, education, and water and sanitation. Read his first post here, or follow Tom’s trip on Twitter at #tom_UNICEFUK and @twhiddleston.

To set the scene. Since we left Conakry, we have been driving east, driving deep into the most impoverished parts of the country, where terrain is arid, burned and rough. The road is red and dusty. On either side the land is dry and charred. We are heading east towards the border with Mali, which is closed and too dangerous for us to approach because of current instability. We won’t go as far east as that, but it’s instructive to see the poorest and most remote parts of the country, because child malnutrition, education and access to clean water will be at their worst out there.

The road is riddled with potholes, with deep trenches on each side, edging incrementally towards the tarmac, as if some terrifying creature from ancient myth had taken a huge bite out of the side. It’s difficult to drive at speed, in spite of the paucity of other vehicles on the road. For one hour, you just ride it out. After six hours, your back is twitching and your head is swimming. Occasionally we pass local taxis with every inch of space is taken up by passengers. Occasionally we pass a fuel truck, snaking at a snail’s pace around the scattered potholes like a minefield. I came expecting conditions to be hard – it appeals to my sense of adventure. I have no signal on my phone, I have nowhere else to be, I’m cut off from the rest of the world, and all I have are my thoughts and the great conversation of the team for company. It feels like borrowed time. Staring into the overarching sky. But of course the period of endurance is finite for me. In a week’s time I’ll be back in London, able to choose between the tube, a taxi, a car or bicycle to rush around at high speed. For local Guineans, this is life. These are the conditions they have to live with every day of their lives. These are the distances they have to travel: to get food, to get fuel, to wash their clothes in the river. It’s a sobering thought.

In other news, my French is improving. Inevitably there are many local languages and dialects depending on the region, but French is mostly the order of the day, especially when communicating with local communities and medical authorities. “Il faut parler en français”. Vous êtes sur?, they say. “Oui absolument, je comprends plus que je parle, mais je comprends la plupart des choses.” Necessity breeds capacity. If I want to understand, I need to listen. And besides, it’s fun.

On the French-speaking front, I was out of the frying pan and into the fire. On the morning of my third day, we were invited to the rural radio station of Bissikirima, which reaches the inhabitants in the region of Dabola in Guinea, covering some 171, 983 people. The Bissikirima radio is financed and funded by UNICEF, who also make provision for technological equipment, but it is staffed by local authority-figures of energy and eloquence. We were greeted warmly and ushered into the studio to watch a live broadcast, l’émission. The ebullient DJ welcomes two guests into the booth, and in between musical interludes, they discuss local affairs, but also broadcast important information about some of the key issues I’ve already touched on: water, sanitation, breast-feeding, childhood immunization and education. It suddenly makes me think of BBC Radio 4 and the Today programme, or NPR in the USA. The radio here keeps people informed, in touch and in the loop.

Crucially, though, the community is engaged in dialogue with itself. The mothers listening on the other end, living in the remote parts of the country have no idea that UNICEF is affiliated to the program. They are simply listening to their favourite radio DJ, who happens to be discussing the importance of water and sanitation, and the upkeep of local latrines. The same goes for the ten-year old-boy who has parked his bike by the river and is listening along on his portable transistor. Perhaps he overhears a broadcast about hand-washing. Perhaps it strikes home. UNICEF have found a unique way of helping the local community to set themselves up to be self-sustaining and self-educating. But the helping hand is invisible, just as when the UNICEF vaccines arrive in the villages to immunise new-born children against disease, without any branding on the syringes. The mothers, nurses and doctors do not know where the vaccinations come from, but they do know for sure that they come.

Ten minutes into the broadcast, there’s a phone-in. Anyone can call the helpline, and the DJ and his colleagues are there to answer their questions. It’s a brilliant idea. (Orange, the telecommunications company, has a huge presence in Guinea. It’s the only advertising I see across the country. Many cannot sign their own names; but they all have a mobile phone). Moments later, I am invited into the booth to say hello to the listeners of the region of Dabola. It’s one thing speaking my long-forgotten and broken French when conversing with a hospital doctor; it’s quite another to suddenly be addressing untold numbers of local listeners live on air, in my capacity as a UNICEF supporter. All I can do is thank them for welcoming me, and I make a promise that I will share everything I see and learn with my friends and colleagues, that I will spread the word, and bring the problems of Guinea to the attention of the UK, and thereafter the world. The radio at Bissikirima is another tool for communication and education. It’s one more drop in the ocean, which might one day turn the tide.

Communication is the key. After the broadcast I am introduced to a kindly, lean, venerable man with a greying beard, dressed in mauve silks. He is a “traditional communicator”. He has come to tell us how he conveys similar messages to those who perhaps don’t listen to the radio, nor pay any heed to the advice of the local DPS (the chief medical officer) or UNICEF representatives after they have gone. He asks if we would like a demonstration of how he talks to more conservative members of the community about their problems. I would like that very much. “Very well,” he replies, “this is how I talk to the grandfathers about the girls who cut themselves”. His last words hang in the air. I don’t quite understand and have to turn to Pauline for further clarification. He is going to tell us how he combats the continued practice of the genital mutilation of young women. It takes a moment to fully understand this. I am profoundly shocked to hear that there is such a practice. But he is already on his feet. He’s a terrific actor.

“Where do you receive the power?”, he booms to his colleague (playing the grandfather), “where do you receive the power to tell the young women what to do with their bodies? Do you want your daughters to spend the rest of their lives in pain? Do you want your daughters to spend their lives crying into the night? And do you want your daughter’s daughters also to spend their nights crying in shame?”

95% of the women in Guinea are victims of genital mutilation. The practice is overwhelmingly the norm. Still more shocking is the fact that it is customarily performed on younger women by older women. It’s a rite of passage from childhood to adulthood: a ritual that is supposed to prepare a woman with a capacity to endure pain; a signal lesson that pain is a constant, and must not be yielded to.

The traditional communicator tells me the custom stems from the myth of Abraham. Abraham had two wives, one older, one younger (the younger having previously been a servant to the older woman). But his first wife was always jealous of the second wife – jealous of the love and affection bestowed upon her by Abraham. This was exacerbated by the fact that the first wife bore Abraham no children, while the second wife gave Abraham two sons: Isaac and Ishmael. In a fit of jealous rage, his first wife “cut” her rival, in order to make her seem less attractive and less desirable to Abraham. But Abraham’s love for his second wife did not diminish after she had been cut. His affection for her perhaps even increased. Uncomprehending and in despair, his first wife then inflicted the same mutilation upon herself. “And that is why this is the custom among women,” says the traditional communicator.

Whether most Guinean women know this story from folk history is another question, but what is disturbing is that they perceive the practice of female genital mutilation (l’excision) to be normal. It’s hard for UNICEF to strike the right balance in helping educate young and older women about this issue, especially because male circumcision has been proven significantly to reduce the risk of contracting HIV. But they are working with traditional communicators, who are trusted senior figures in rural communities, to spread the word among women that the practice of genital mutilation immeasurably increases the risk of mortality and disease in their children. It may affect the pregnancy and the health of their child. These mothers need help. Il faut aider et encourager les mamans. I realise with startling clarity once more: help the mothers – and you help the children.

Our next stop is the remote village of Loppe. We park up by the road. It’s a mile-long walk to the village through the bush. Halfway along the path a distinguished gentleman in an impeccable khaki suit and tie pulls up on a motorcycle and tells me to hop on the back. On attend la delegation. Riding pillion on the back of a motorcycle through West African countryside under the midday sun delivers a shot of speed and adrenalin. It blows away a few cobwebs. It’s great.

The atmosphere in Loppe seems peaceful and happy. We are here to visit UNICEF’s sanitation program and the latrines. The central imperative in a remote village like Loppe is to separate water sources, to keep access to the water wells clean, to protect them from run-off from the land in the rainy season, which is contaminated by animal waste, and guard the mouths of the wells from the animals themselves. We are also shown several defecation points. The UNICEF program has helped to implement key practical design developments: providing concrete covers over the latrines to keep the flies out, building concrete walls to keep the animals away, provide kettles full of water and a bar of soap to wash your hands afterwards. If there’s no bar of soap, there’s a bucket of ash that will do the trick. This basic hygiene and good sanitation raises the standard of general health, and protects mothers and children from passing on disease.

What happened next was the most uplifting experience of my journey so far. I was invited by a young family into their home. They live in a circular hut, under which is one singular room, with a circumference of about fifteen feet across. The roof is thatch made of straw. Inside I am introduced by Idrissa, the regional chief of UNICEF’s office for Eastern Guinea, to a couple and their three children, a boy and two girls. They are uniformly beautiful. The father is calm and quiet, with an open handsome face, while the mother is shy, her skin radiant, and a smile that could launch a thousand ships. Her children are well behaved, quiet and curious. Idrissa asks if I have any questions. I compliment them on their house, for it is beautiful inside. There is a bed, which serves also as bench and table, with various tools and pots hung strategically along the walls. I say how well her children look, how strong they seem. Her elder daughter reminds me of my niece. I ask if there have been any problems at all in their upbringing and nurture. “No,” she says simply. Were they born at the centre de santé? “No,” she says, “they were all born at home.”

I ask if she had easy access to vaccinations. “Yes,” she says. “The day they were born”. She says their biggest problem is that they do not have enough food. They work hard, and still there is not enough. But they grow their own rice-crop and haricots. Pauline asks if she was able to breastfeed her children. “Yes,” she says, “for six months each of them”. How did you know to do that, I ask. “I walked to the centre de santé,” she replies, “when I was pregnant. They told me I should breast-feed. Also I heard it on the radio”. That’s fantastic, I say. I tell the father I have been looking at the water situation in the village, and the new program for better water hygiene. He replies that it’s very important. He always tells his son he must wash his hands before eating. I tell him his boy is looking strong, and that when I was a child I was always taught mens sana in corpore sano. A healthy mind in a healthy body. Idrissa translates. The father says this has made his day. It is a great honour for him. He is happy.

It is heartening and stirring to talk to a family who are doing it right, and who are taking responsibility for themselves and for their children. The team at UNICEF find it deeply inspiring, as do I. The messages are being heard. It’s working.

The residents of Loppe give us a rousing send off by bursting into song as our convoy of motorbikes rev their engines and rocket off into the low afternoon sun. Buoyed up by our visit, there’s time for a piece of bread and a slice Vache Qui Rot cheese from the cool box, washed down with a can of coke and a tablet of malarone.

Then commences the long drive to Kankan. We pull on to the road, where our only company are the wandering cattle, who have become commonplace as traffic lights. Lethargic and listless, they look like they’ve been roaming the roads of Guinea since the dawn of time. And no doubt they will continue to long after we’re gone.

насыщенная общественная жизнь

отсюда

Поделиться812013-01-30 22:08:43

и вот сидит наш путешественник, практически как Ленин, в москитной сетке, и пишет дайри

На второй просто шахтер!)))

путешествие Тома продолжается

Вай, на моцике сидит!  Опять эта клетчатая рубашка!)))

Опять эта клетчатая рубашка!)))

Tom Hiddleston’s Guinea field diary: Day 4

It’s day four for actor Tom Hiddleston on his first trip with UNICEF UK, visiting Guinea in West Africa. Tom will be meeting with Guinean children, families and communities. He’ll also be seeing several UNICEF projects, and finding out about our work in child protection, education, and water and sanitation. Read his first, second and third posts, or follow Tom’s trip on Twitter at #tom_UNICEFUK and @twhiddleston.

My fourth day begins with a run. We are in Kankan. Julien knocks on my door at 6:45am. I haven’t slept much, because it’s only at night that I have time to write. But I’m only here for a short while. It’s important to make the most of it. Julien and I run along the river. At this hour, the streets are already bustling with activity, but the riverbank is deserted. In a few hours’ time it will be almost as busy as Oxford Street. People will come from all over town to wash their clothes, their cars, and their bodies. Perhaps it’s because it’s very early in the morning, when the mind is clear, when our thoughts are unfettered by politeness and self-censorship, but Julien and I end up discussing our passions.

I share my admiration for Shakespeare, while Julien speaks with erudition about philosophy. He’s a big fan of Michel Foucault, the French philosopher who said (among many other things): “I don’t feel that it is necessary to know exactly what I am. The main interest in life and work is to become someone else that you were not in the beginning.” Every day is a creative act: a step closer to becoming who you want to be. I admire Julien enormously. He believes unwaveringly in the nature of public service. He believes in the power of legacy. He believes in leaving behind a better world than the one he found. He believes, quietly but fervently, in that attempt.

As the resident representative for UNICEF in Guinea, one of Julien’s greatest achievements is a project for the reintegration of children who used to be in the army, supported by the Peace Building Fund. It was our first visit of the day. In early 2011, working closely with the Minister of Youth, Julien personally persuaded the Prime Minister to approve a project to support 2000 young people who had been irregularly recruited by the armed forces. These children are essentially former child soldiers, although they have not seen actual conflict. They are young people in local communities in remote, rural areas who at the age of 15 to 17 who were recruited, some forcibly, and transported to military camps for training. They were not allowed to leave the camps and those who attempted to do so were beaten, physically punished, humiliated and deprived of food. In 2010, with the transition from military to civilian rule, these young men and women were released without any means of subsistence or transportation. In fear of stigmatisation, many of these children – frightened, scarred, adolescents – some of whom fell into crimes and banditry. Other vulnerable youths who had been affected by the conflicts in the region were recruited into the programme.

The Peace Building Fund paid for their reintegration through the government’s Professional Training Centres which although reasonably equipped did not have the money to run training programmes. The project aims to facilitate the reintegration of what are now young men and women through vocational training services. The centre is a hive of activity. As I get out of the car I am directed to a quadrangle of workshop buildings, specialising in different and specific skills: woodwork; welding; plumbing, carpentry; training for electricians; brick-laying and masonry. These young adults are consumed with purpose. I’ve never seen craftsmen and women so proud and passionate about their work.

I speak to Claude, in the woodwork shop, who has been making chairs and tables and doors and beds here for the last two years. Later, in a quiet room in the Director’s office, Claude tells me his story. He was in his field. He was working on his crops. The military came and said to him: “You’re coming with us.” And that was it. When the troubles were over the army let them go he went back to his fields. When this project, the Peace Building Fund, came to him and offered him a second chance, his first response was: “No. I have been disappointed once. What are you really going to do? Je n’avais pas confiance.” But then he thought he might be able to make a success of it and decided to give it a try.

Claude has never looked back. When he was trying to get recruited into the military in his late teens, his mother had approved. He had hopes of getting a job, of earning money, of receiving training. He received nothing. But he got lucky. His final words are rousing: “I spend all my time in my workshop now. This is my life. This is what I do. Here, now, then, after. If there is wood, if I have my equipment, I will always be able to work. I love it. I own money. I am here.”

This doesn’t happen only to the boys. I also speak to Josephine, who is from exactly the same village as Claude. In between 2000 and 2007, she was studying. But her father passed away and she was alone with her mother. They were selling vegetables at the market. Nearby there were a lot of army camps. They came to her village and they were looking for new recruits. The army came into her house and told her that the location of their base was a secret and that if she revealed it they would kill her. “Ils vont tuer ma famille.” She was hired. She followed the soldiers into the bush to act as a cleaner: she had no options. It was hard, but she says she “got used to the sound of rifles.”

When the Peace Building Fund came to her, her mother warned her against it: “They are going to abuse you. They are recruiting you because of the boys. It’s too dangerous.” She pleaded with her mother. She said, “God is big.” Now Josephine is happy: she has skills, she is confident, she has money to share, and no worries for the future. She is so happy it makes her want to cry.

What UNICEF is doing for these young adults is enormous. The Centre de Formation is providing them with a vocational two-year training programme that will give them a purpose and a source of income for the rest of their lives. Kankan needs plumbers, electricians, carpenters, and builders. These are the technicians who build a society. And they will build their own.

In the afternoon, we drive east from Kankan to Mandiana. It’s 35km as the crow flies to the border with Mali. It is the most remote place I have ever visited. The road is not a road at all. It is a dirt track through the bush, more uneven than any so far. The journey takes two and a half hours in our 4x4. When we arrive, my first question is:why? Why is there a settlement here? I can’t immediately understand the history of the place. There is no river and little vegetation.

The answer: gold. There are artisanal gold mines around Mandiana, which create a primary source of income for the men in the region, who scratch a living panning for the precious metal. We are here because it just about the furthest from Conakry that you can possibly travel, and UNICEF nutrition surveys have shown malnutrition in this area is at its worst. We park outside the Centre de Santé, which is full of women and children, and as soon as we’re inside, quite spontaneously a focus group seems to begin. These women are more direct and straightforward than any I have spoken to thus far. They seem less encumbered by shyness or mistrust. They are angry and their problems are urgent. What is the biggest problem for you here, I ask. Water, they reply. There is no water. The statement is so basic and baldly stated it hits me like a club to the head. Can you talk more about that, we ask. One woman speaks up. There is only one well, it is a long walk from the village, and we only have access to it for certain hours of the day because it is controlled by the military. I don’t need to expand on this. They are deprived of a basic need.

What follows is a demonstration of the methods of screening small children for signs of malnutrition. The first test is relatively simple. A small coloured band, like a bracelet or an ankle belt, is threaded around the left arm of the child, between the elbow and shoulder, to measure the width of their upper arm. If the measurement is in the green zone than all is well, in the yellow or red then there is cause for further treatment as the child is either moderately or severely malnourished. If a child is diagnosed to be malnourished, they are immediately treated by the centre de santé or referred to the local hospital which treats the most severe cases of malnutrition where there are also other complications. These complications may have caused the malnutrition, they may be a result of malnutrition, or they may have exacerbated existing malnutrition. Whatever the case, these are very sick children.

Moderately malnourished children are firstly prescribed with a peanut and protein-based packet of paste, with a consistency like cake icing, which is given to the mother to feed to the child, a certain quantity every day. It also contains essential vitamins and minerals, and the hope is that when the child returns to the health centre in a week or two weeks’ time, it will have increased the child’s level of health. If a child is severely malnourished he will be admitted immediately to the nearest in-patient centre or hospital and prescribed with a treatment of fortified therapeutic feeding milk: F75 and F100 which vary in strength and is given during the two main Phases of treatment. UNICEF is responsible for providing and supplying this milk and medical equipment.

The eight-month-old boy that is tested registers on the border of the yellow and the red zones. He’s diagnosed moderately malnourished. And there is no water here. He’s only eight months old. The road ahead of this young boy is unimaginably steep.

We are taken across the village to the hospital in Mandiana. There are twelve beds; four of them reserved specifically for children with malnutrition. We’re introduced to a young mother, eighteen-year-old Alima Diallo and her one-year-old son (her third child) who has been receiving treatment at the hospital for the last two days. He has malaria and he is also severely malnourished. Perhaps the former led to the latter. Alima’s first child died at fourteen months, probably from malaria as well. She lives 9 km from Mandiana, and regularly comes to this hospital: “Here they do good work.” The doctor explains that they provide therapeutic milk firstly, then medicines and antibiotics. They also provide folic acid to improve condition of blood, paracetamol to reduce fever, and tablets to reduce parasites. Multi-vitamins as well. A lot of meds.

The doctor needs to see 15% weight increase before the child can be released, which should take three weeks, after which Alima can go to the health centre which will reassess the child’s health status and could provide the specialized peanut paste.

In this scenario UNICEF provide the peanut paste – this particular brand of which is called Plumpy’nut, and has been used here since 2007 – as well as the training sessions for the doctors on severe acute malnutrition: instructions on new protocol; cooking demonstrations for young mothers; sessions on how to implement support groups for breast-feeding women, formula milk, arm measurement tapes, and weight scales. UNICEF provided the equipment and the supplies, but local medical staff save lives.

Alima is very happy about the treatment she’s received and she can see the improvement in her baby. The doctor says it’s likely that Alima only spent three years at school. She thinks she’s doing it right, but the doctor disagrees. Alima thinks she has enough food, when she doesn’t. Alima is a child herself. She’s 18, and has borne three children. She had her first child at the age of fourteen. The child died. Her second is three years’ old. She suspects he has malaria. Her third is malnourished.

As we walk away from the hospital Julien explains that this looks like a case of a young mother not knowing how best to ensure her child has a balanced diet, is protected from water borne diseases and malaria.. She lives far from the health centre, has missed out on a primary school education in general, and specifically in observing and diagnosing the symptoms of ill health. She has probably responded too slowly and too late in seeking medical assistance. Alima has done the best she can with what she has, but has been let down by a lack of education. She is learning, however. She says she won’t be having any more children until her youngest is healthy.

As we drive away from Mandiana, from this hot, barren place, I feel further away from home than ever. I can’t conceive of what life must be like there on a daily basis; and the simple challenges they face to survive. ‘There is no water’. I can’t get it out of my head.

Что-то из старого всплыло)))

Большое интервью Тома!

Первый кадр из фильма "Выживут только любимые"! Если бы не знала, что это Том, ни за что бы не поверила! Я ведь сначала подумала, что это молодой Гэри Олдман!

Поделиться822013-01-31 06:05:32

Julien knocks on my door at 6:45am. I haven’t slept much, because it’s only at night that I have time to write.

бедняга, всю ночь пишет свои мемуары, а в 6:45 уже труба зовет, вот режим-то

Если бы не знала, что это Том, ни за что бы не поверила! Я ведь сначала подумала, что это молодой Гэри Олдман

при первом взгляде так и кажется! неужели они собираются эксплуатировать этот образ, ну что ж такое, сразу же будут сравнения - никуда не деться от них. почему не постарались придумать хоть что-то новое в облике? ну, я аж опечалилась, блин.

вот фан-арт еще есть

Ссылка

и гифка из интервью

Ссылка

Поделиться832013-02-01 08:31:50

Tom Hiddleston’s Guinea field diary: Day 5

Tom Hiddleston, Thu, Jan 31 2013 3:51 PM

It’s the last day of actor Tom Hiddleston’s trip with UNICEF UK to Guinea in West Africa. Read his first, second, third and fourth posts, or follow Tom on Twitter at #tom_UNICEFUK and @twhiddleston.

Day five is the day we drive. We drive west. We are in Kankan. We have a plane to catch tomorrow, and Conakry is just under 400 miles away. There’s no three-lane freeway or motorway. It’s the same old road. The dirt, red road. We drive.

We talk, we listen, we look. Along the way we make various stops. We stop at a town to stretch our legs. We stop to sit under a tree for some shade, for bread and vache qui rit. We stop just after recrossing the river Niger, when Julien spots something on the roadside. It’s a monument, inscribed with this message:

ICI.

Le 6 Novembre 1999.

Les femmes ont librement

solennellement

et definitivement deposé

le couteau de l’excision.“Here. On 6 November 1999, the women freely personally and definitively put down the knife of cutting (of mutilation)”. Interesting, says Julien. The monument was erected in 1999. And yet we heard about it extensively two days ago at the radio station in Bissikirima. Female genital mutilation (FGM) isn’t over. It isn’t over in Guinea. It isn’t over in many countries, all over the world. It isn’t over.

Then we’re back on the road.

Our next stop is a joyful one. With the river some 115 km behind us, we pull in to a school in Kouroussa – L’École Primaire Layiya – on the edge of the National Park of the Upper Niger, which is still in the region of Kankan. It’s greener here than before, the land is less arid and the trees are full. It smells fresh.

It’s worth bearing in mind that 74% of boys and girls in Guinea enrol in primary school, but only 63% make it to their final year. At Layiya, there are approximately one hundred and thirty children, learning how to read and write, learning French, learning maths. Their education is their freedom. I think back to those children I saw on my first night in Conakry, reading by the electric light of the car park by the airport. In Guinea, children want to learn. Education is power.

We are introduced to several classes of the most well-behaved, quiet, attentive and sweet children I’ve seen since I’ve arrived. A little girl, in a red-checked school dress and braids in her hair, is so shy and smiley that she can’t even tell me her name. I must look like an alien to her. Some brave souls volunteer how old they are, and what they’ve been studying. An even braver soul at the back tells me what he wants to do when he grows up: “Après avoir terminé mes études, je veux devenir enseignant.” He wants to be a teacher. It gets a round of applause.

It’s 12:30pm. It’s almost time to break for lunch. Julien asks who wants to play football outside before break. There are instant smiles. One young man at the front puts his hand up immediately. There is a spark in his eyes. He’s almost embarrassed by his own enthusiasm, but he couldn’t hide if he tried. This young man loves football. And he’s the smallest boy in the room.

It turns out he’s a firework. I thought we were going to play a game, but for the moment it’s clearly just him and me. He runs rings around me like Lionel Messi. He makes me feel like an ogre (I am an ogre). He’s amazing.

But then it’s time for a real game. Captains are appointed (he’s one of them). Teams are picked. The entire class is huddled in a group in the small crescent yard outside the school. Everyone is in: boys and girls. Julien and I are the last to be picked. On opposing teams. All as it should be.

It’s so fun. It’s just like any other game of football in any other school anywhere in the world: frantic, breathless, playful. The scuffling of shoes, the groaning when you miss, the laughing when you fall over. Dust rises in the yard, so thick that you can’t see the ball. It’s baking hot. And these children run like lightning. In a fitting end, Julien scores the winner as a result of terrible defending by me and an abject failure to clear my own goal line. For them it’s time for lunch. For us, it’s time to go.

Later in the afternoon, closer to Conakry, we stop to visit the École Moriakhory, in prefecture of Kindia. We are introduced to Gervais, the education officer here. A kindlier man I may never meet. The École Moriakhory, using funds from UNICEF Guinea, became a pilot for the scheme before the grant for the FTI programme began. The Programme Sector of Education in Guinea was adopted in 2008, but due to the suspension of foreign aid by major donors, its implementation was greatly hampered. Following a plea for funding, the Fast Track Initiative was established. UNICEF became a supervising entity and operator. The Fast Track Initiative has helped construct 991 classes in 300 school buildings and equip them with latrines and water points. The latrines are a work in progress. The initial design employed a separation system of liquids and solids, but it depended on human agency to clear the solids and use them as fertiliser for crops. The job was unpractical and unpleasant. So it’s back to the drawing board. But they will find something that works. That’s what UNICEF do. The Fast Track Initiative is also replacing the old school tables and lecterns, too high and heavy for children to move themselves, with lighter, more durable desks, benches and chairs. Slowly but surely, the facilities in these schools are rapidly improving. The Fast Track Initiative has also built 60 pre-school classes. These schools contribute to the literacy of 50,000 children across Guinea.

The children in École Moriakhory are obedient and alert. I enter one classroom and there’s no teacher in there. But they’re all sitting quietly. It occurs to me that it was never like that when I was at school in England. If the teacher left the room, there’d be a riot. Here, children want to learn. There’s a poem on the blackboard. It’s about Guinea. Can we all recite the poem together, Julien asks. And we do. The lyrics are beautiful. I wish I could remember them. I wish I’d taken a photograph of the blackboard. The poem was about their country. La Guinée est un beau pays. Un beau pays. Something like that.

As we pull away I feel glad that on my last day I saw such a joyful example of UNICEF’s work in Guinea. The country has many difficulties, and I have faced them in all their stark reality this week. But to see healthy children, in love with learning, and happy in their play is restorative and invigorating. It gives me a sense of balance.

Un beau pays.

Поделиться842013-02-02 13:15:04

вот и завершилось путешествие

Tom Hiddleston’s Guinea field diary: back in London

Tom Hiddleston, Fri, Feb 1 2013 3:08 PM

Actor Tom Hiddleston has just returned home from his trip with UNICEF UK to Guinea in West Africa. Read his first, second, third, fourth and fifth posts or follow Tom on Twitter at #tom_UNICEFUK and @twhiddleston

So that’s it.

I’m back in London. I am back in my home. Back amid the hustle and the bustle. Back amid the humdrum and the mayhem and the madness. Back to running water and the warmth of central heating. Back to a bed without a mosquito net. Back to food in the fridge and food in the cupboard and food around the corner in the supermarket.

I’ve seen things I have never seen before.

When I started writing this blog, I talked of life in Guinea as a “jigsaw puzzle, one where the pieces keep moving or changing shape, which in turn alters the picture. You might be looking at it from a different angle, or at a different time of day”. On my first night, Julien had suggested an idea of reality in Guinea as “open to interpretation”. In so many respects, that is true of all life. The view always changes with the viewer. That’s the law of relativity.

Here’s what’s not open to interpretation. Every year in the world more than two million children die of hunger. It shouldn’t be like this. Children in Guinea start life at a severe disadvantage. Those that are malnourished may survive in the end. If they are caught in time. If their mothers respond to symptoms early enough; if they make it to the centre de santé, which is often miles away; if they respond to the therapeutic peanut paste, and special therapeutic feeding milk. If their parents are able to grow crops and feed them with enough nutritious foods so they can keep healthy. If they win the fight against malaria. If they live near a good school. If they can get work. If their parents can protect them from exploitation by the military. If they are lucky. Previously malnourished children can make it. It sounds paradoxical to say it, but they are the lucky ones.

Malnourished children grow up at a disadvantage. They will be physically smaller, possibly with diminished intellectual capacity. Their brains and bodies won’t develop in the same way. Of course, there is always a chance that through hard work, education, training, and strength of will any individual can and will progress to great achievement. But these children start so far behind. The race of life – the race for life – is infinitely longer and infinitely harder. Every day there are challenges to their survival and development. Context is important. I’ve been privileged enough to have seen that context at first hand. They live in the middle of nowhere. There is no water. There is poor sanitation. There is a shortage of food. There is lack of education. Conditions are inconceivably hard: they are incredible, until you have seen them with your own eyes, until you have lived in their midst, even for the shortest while.

Before my visit to Guinea, I knew that global hunger and malnutrition was a problem. But the issue was only academic in my mind. When you’ve seen malnourished children with your own eyes and their disadvantaged start in life, a moral imperative compels you to act and becomes impossible to ignore.

In the west, we take our simplest privileges for granted. Many have said this before me; and many will say it after me. It’s still true. In the very poorest regions of West Africa you can forget about a nice shower or warm bath at the end of a long day. About flushing the loo, or even having a loo to flush. You can forget about turning on a tap. About dashing round to the shop to buy newspapers, a bar of chocolate and some washing powder. In Guinea, people walk 15 miles to the river to wash their clothes. Washing your clothes takes all morning. You don’t just ‘put a wash on’.

I am no saviour. I’m absolutely the last person on the planet who can practically help. I don’t know how to make the different types of therapeutic feeding milk. I’m no chemist. I’m no doctor. I’m no engineer. I can’t manufacture polio vaccines or organise their transportation to the health centres in Saramoussayah or Bissikirima. I can’t build schools, or design drainage systems. I can’t provide the women and children of Mandiana with water.

I’m just an actor. Interestingly, there’s no such thing as an ‘actor’ in Guinea. It simply doesn’t register as an occupation. I heard tell of the ‘griot’: the term used in West Africa to describe the storyteller, the poet, the bard. But at the schools I visited when I asked children what they wanted to be when they grew up the answers were “teacher”, “minister of education”, “plumber”, “electrician”, “carpenter”, “teacher”, “teacher” and “teacher”. Many even said they wanted to work for UNICEF.

The people who are really helping are those on the ground. They are heroic, and mostly if not entirely unsung. Julien Harneis, the resident representative of UNICEF in Guinea and our guide, is a man of extraordinary learning, experience, energy, curiosity and kindness. It’s his job to divide UNICEF’s financial and medical resources and to make sure those plans and policies get real results in the field. It’s his job to coordinate with the Guinean government and local authorities so that advances in both the humanitarian and developmental imperatives of the country rise in parallel. He is helped by Felix Ackebo, his deputy, by women like Michele Akan Badarou, his communications specialist, by Dr Pierre Andou, his nutrition specialist. It’s people like Idrissa Souaré, Chief of the East, and Mariame Kanka Labe Diallo, the directrice professionelle de santé of Saramoussayah, who made such a lasting impression on me. I’ll never forget her face as long as I live. These are the people who are doing the work, day in, day out. This work is not morose or maudlin. It is joyful.

Then there is Pauline Llorca and Louise O’Shea, indefatigable, inspirational and ceaselessly kind, and their team at UNICEF UK in London, who work so tirelessly and with such passion to promote, develop, and implement UNICEF’s policies and programmes all over the world. It is to them that I owe an eternal debt of gratitude. It is they who allowed me the privilege of visiting Guinea. They made it possible.

What I learned in Guinea is that we are all responsible for the state of our world. The world – and the system by which we trade, share, cooperate and conflict – is clearly not working. We are only as strong as our weakest members. UNICEF is run at every level by strong, relentlessly energetic, deeply capable people who use that strength, energy and capability to help those who need it most: the weakest, most disadvantaged women and children of our world. All I can do now is help make people aware of what is happening, of what they are doing. That is all that I can do. For now.

Did you know that this year, UNICEF UK is joining forces with over a hundred charities to campaign for a fairer food system as part of the IF Campaign?

We’re asking the UK Government to take action so that children don’t have to wake up hungry. Together, we can make 2013 the beginning of the end of world hunger. Have you signed up yet?

Поделиться852013-02-04 20:40:35

вот и завершилось путешествие

Господи Боже мой, что с ребенком на последнем снимке?!?!  Том закончил творить добрые дела в Африке, но продолжает творить добро в Лондоне!

Том закончил творить добрые дела в Африке, но продолжает творить добро в Лондоне!  Скоро нас ждет новая фотосессия! А пока можем полюбоваться фотографиями "за сценой")))

Скоро нас ждет новая фотосессия! А пока можем полюбоваться фотографиями "за сценой")))

А вот маленький мальчик заловил Тома в "coffee shop")))

Поделиться862013-02-07 10:02:52

Скоро нас ждет новая фотосессия! А пока можем полюбоваться фотографиями "за сценой"))

фотки очень нравятся, сами уже как готовый фотосет

а вот этот же фотограф, Jason Hetherington, выложил у себя в фб снимки "в процессе"

Ссылка

фотосет будет для Flaunt - самого "жестокого" журнала в мире

как они там над нами издеваются, кошмар....

Поделиться872013-02-08 16:37:59

для всех, кто любит ушами

Поделиться882013-02-09 00:59:02

С ДНЕМ РОЖДЕНИЯ, ТОМ! Желаем тебе счастья и всего самого лучшего!!!

Видно со сборов Тома в Африку с русскими субтитрами!

Поделиться902013-02-11 05:46:12

Том на Бафте

красная дорожка

пресс-рум

Ссылка